Over the past few years, low Earth orbit (LEO) has become noticeably more crowded: thousands of satellites now support communications, navigation, and Earth observation 🛰️. Recent studies suggest that this growing density is no longer just a background statistic. Researchers have examined what could happen if satellites were to temporarily lose their ability to perform collision-avoidance maneuvers—for example, due to a powerful solar storm or a large-scale systems failure.

To describe this risk, scientists proposed a metric called the CRASH Clock—a conceptual “timer” that estimates how long it would take for the first serious collision to occur if active orbital control were suddenly lost. According to current calculations, by 2025 this window has shrunk to just a few days—roughly 2.8 to 5.5 days ⏱️. For comparison, similar scenarios were estimated at several months as recently as 2018. This is not a prediction of an imminent disaster, but a way to show how much smaller the safety margin in orbit has become.

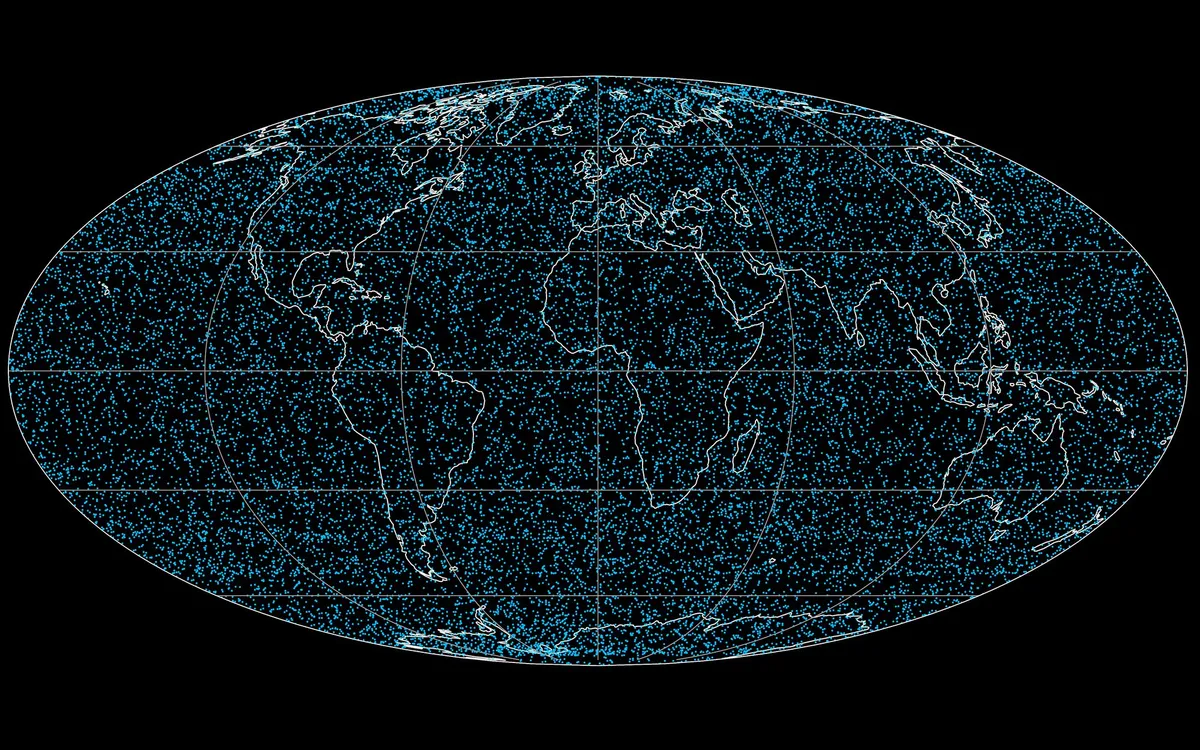

Each dot in this plot represents a tracked object in low Earth orbit.

What stands out here is how dependent modern orbital operations are on continuous maneuvering. Most satellites in LEO regularly adjust their trajectories to avoid close approaches. As long as these systems are functioning, the environment remains manageable. But if control is disrupted even temporarily, the sheer density of objects starts to work against the entire infrastructure ⚙️.

In practical terms, this means the risk associated with the Kessler syndrome—a cascade of collisions generating ever more debris—has become more sensitive to external disruptions. For satellite operators and regulators, this is a reminder that orbital sustainability today depends not only on how many spacecraft are launched, but also on the reliability of control systems, coordination mechanisms, and rapid recovery after failures. For everyday users of satellite services, this does not change anything directly for now, but it highlights how fragile the underlying space infrastructure can be 🌍.

There are important caveats as well. The CRASH Clock estimates only the time to the first potentially serious collision, not a full orbital collapse scenario. In addition, parts of the analysis are based on models and preprints that are still being discussed within the scientific community. It is best viewed as a careful analytical signal—not a claim that dramatic events are about to unfold in the coming days.

Sources:

— IEEE Spectrum — overview of the CRASH Clock metric and researcher commentary:

https://spectrum.ieee.org/kessler-syndrome-crash-clock

— Earth.com — analysis of solar storms and satellite density in LEO:

https://www.earth.com/news/earths-satellite-networks-may-be-one-disruption-away-from-disaster/

— SciTechDaily — accessible summary of time-to-collision estimates:

https://scitechdaily.com/2-8-days-to-disaster-low-earth-orbit-could-collapse-without-warning/

— Wikipedia — background on the Kessler syndrome:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kessler_syndrome